The Price of Playing the Best Deck

We all like to play the best deck and get the best results, it's an unavoidable maxim of competitive Magic, and typically, the player with the best archetype tends to be in the Top 8 most often at major tournaments.

Magic is an ever-changing game, especially at a time when we have more and more releases coming out in a shorter amount of time, and more players following and playing constructed formats in both local stores and the Online environment. And when we talk specifically about tournaments, we consider a significant portion of players who have two goals: to improve their experience with the game, decision-making and their familiarity with the list they are running and, preferably, win the tournament.

Ad

Playing with the best deck means increasing your odds of winning if you know how to pilot it correctly (as usually the rest of the Metagame will be against you), and most of them reward you a lot for making good decisions during the game, as well as to offer a strategic advantage in relation to the other archetypes.

This, however, also comes with a price that goes beyond the monetary value invested in the cards, together with a chain reaction driven by its representation in tournaments, in the coverage spotlight, guides and discussions on forums and websites referring to the most efficient ways to defeat it, and occasionally, we also pay the ultimate price: Bans.

Recently, Naya Winota was banned from Pioneer a few weeks before the Qualifiers season for Pro Tour: Dominaria United, generating a huge backlash from the community, who felt compelled to abandon the format because their archetype ceased to exist, and most of its cards won't usually co-exist in other strategies in the format's competitive scene.

Unfortunately, these situations do occur and there is not much we can do about it other than to seek to mitigate the damage. But bans aren't a new thing, and we can learn from them, especially about how to invest our resources and how to avoid being so largely harmed by them.

As an example, I've suffered from multiple bans on constructed formats — The Blue Monday, Arcum's Astrolabe, Fall from Favor and Atog on Pauper, Faithless Looting on Modern, Deathrite Shaman on Legacy, Smuggler's Copter, Oath of Nissa, Inverter of Truth and Lurrus of the Dream-Den on Pioneer, Thassa's Oracle and Time Warp in Historic and Winota, Joiner of Forces in Explorer — and being in the midst of so many direct interventions has definitely taught me some lessons about how this happens and how to mitigate that damage, especially at a time when tabletop is making a comeback, and we're actually pouring physical money into scraps of cardboard.

But first, we need to answer an elementary question:

What defines a “Best Deck”?

How exactly do we define what is the best deck in a competitive format? The obvious answer is “the most present archetype and/or with the highest winrate in events” — and that's not wrong because being the best deck is, consequently, getting the best results; otherwise it wouldn't even be a good choice for tournaments.

However, there are two other things that we need to understand: the first is that the Metagame isn't static, and the best deck tends to change as new releases arrive, or as players adapt to the most prevalent strategies and new archetypes become available and set the top of the format. It is very common to see this in Standard, where the card pool is smaller and the amount of games that occur daily in Magic Arena collaborate to solve the Metagame faster — So, when we talk about a “best deck”, we are actually mentioning the most successful strategy at that time.

The second point is that, despite the unpredictable nature of its games, Magic: The Gathering has some repetitive patterns, after all it is simply impossible to create great novelties in a game with almost 30 years of history, and knowing how to identify them helps to understand the game's own nature, and make important decisions when building our decks, purchasing new cards, or even deciding when to play tournaments.

Ad

When it comes to the “best deck in the format”, they tend to follow one or more of these three patterns:

The Good Best Deck — The ones that have a balanced matchup against the majority of the Metagame

Usually, the best deck in a healthy Metagame is the one that has the spells and threats that build the most efficient synergy of the deck, guaranteeing a good mix of answers and threats that allows you to establish a balanced or good game against most other strategies.

I think Rakdos Midrange is a great example of a “good best deck” — it has efficient creatures, some of the best interactions in the format, a powerful value engine and seeks to follow a fair game where it wins by accumulating more resources than your opponent and perform efficient trades each turn.

While I believe cards like Ragavan, Nimble Pilferer shouldn't exist (but that's a topic for another article), Modern's Izzet Murktide follows the same pattern: it's a blend of the best spells and threats available in their respective colors, serves to monitor unfair decks, and collaborates to maintain the format's balance.

Temporary Best Deck — The ones that prey on an unprepared Metagame and establish themselves at the top

Usually, these archetypes suddenly pop up in a big tournament, make good results, more people recognize it as a viable choice and when we look again, it's taking a good part of the Top 8 of various competitive events, content creators are writing about or playing it on streaming, and when you least expect it, it's at the top of the Metagame pages.

It is very common to confuse this category with a broken deck because they appear when a new set comes out, and a new card made a certain proposal possible in that competitive format, and the natural consequence is usually a frenzy of the community to debate this new archetype and even ask for its ban.

The difference is that, normally, this archetype occupies this space at the top because it has a brand-new strategy, the rest of the format is still not used to facing it, and its natural weaknesses haven't been discovered, in addition to it commonly preying on some main competitive lists of the moment.

There are plenty of examples in this category, but the most memorable for me was the 2017 Death's Shadow lists because they entirely changed Modern as we knew it.

Jund Shadow had its big explosion in the format when Aether Revolt brought out Fatal Push, which became an instant staple and gave yet another reward for playing Mishra's Bauble, and the archetype established itself as the best deck in the format because, unlike the classic Jund as we knew it, the low cost of its spells and the high power of its creatures gave it the necessary means to play under the famous Big Mana — Tron and Scapeshift.

Grixis Shadow came a bit later, to catch up with the Jund versions and allow such a mana-efficient archetype to play based on attrition and card advantage by resorting to Kolaghan's Command and Snapcaster Mage, as well as threats that dodged Fatal Push, like Gurmag Angler and Tasigur, the Golden Fang, and it didn't take long for it to establish itself as the absolute best deck in the format and lead even renowned professional players to record videos recommending a ban.

Ad

However, what really happened was that Death's Shadow simply changed the way to play Modern, and previously unviable strategies like Death & Taxes began to rise to prey on its natural weaknesses and, over the years, Grixis Shadow and its other variants have just become one of the main competitors in the Metagame.

In this particular case, it took just over a year for the format to adapt, but typically, the Temporary Best Deck stays in that space for just a few weeks, or a few months.

The Broken Best Deck — The ones that warp formats and have the famous free win button

And finally, we have the one that is so feared by all players, event organizers and, dare I say, even by Wizards of the Coast: the format-breaking archetypes.

Typically, decks that fall into this category do something that circumvents the primary rules of the game, such as mana values, and/or feature what I particularly call a “free-win button” — A combo or play that is so impactful and explosive that it will win the game on its own or put the player in a much more advantageous position than their opponent.

In addition, this category is also characterized by basically forcing the rest of the format to play by its rules, commonly including cards that would belong on the Sideboard or would never see competitive play if it weren't for the specific situation where the environment makes them viable in tournaments.

I suppose nothing in the last decade reflects the nature of a broken deck as much as when Hogaak, Arisen Necropolis was in Modern because it had absolutely everything that categorizes this archetype: it cheated in mana by basically casting their main threat as early as turn 2 almost for free, cheating permanents into play when returning Vengevine and Bloodghast from the graveyard, and still had free win elements and combos with Bridge from Below and Altar of Dementia.

But the broken deck won't always be so evident that it dominates the Metagame, offers an 80% winrate, puts 16 power on the board as soon as on turn 2 and will draw fervent claims from commentators at major events. Typically, it will just offer a more efficient strategy than the rest of the format can handle, with a timid but noticeable advantage over other decks.

I believe this was the case with most recent bans on Pioneer: They weren't exclusively the only viable options for playing tournaments and had their vulnerabilities and bad matchups, but their main strategy was a step ahead of the rest of the Metagame, making it difficult to have a healthy game progress, as an opponent was always forcing themselves to play respecting their “free-win” button, while they managed to take advantage of it by playing a fair game.

That is, the Broken Best Deck is the one that has a clear advantage over the rest of the Metagame in establishing its own play patterns and forcing the other archetypes to adapt to it or lose.

Sometimes they will be notorious and will completely dominate the competitive landscape. In other situations, they won't always have a noticeable advantage over the others, they will be part of the rock-paper-scissors chain of the format, but will offer numerous situations where they just wins the game "for free" due to a specific combination of cards - naturally forcing the rest of the format to play around them.

Ad

Am I playing with a Broken Deck?

The best deck in a format is the one that produces the best results, and consequently, playing with it will give you a theoretical advantage over the other strategies present in the format. But as we've just seen, not every "best deck" will be a "broken deck".

In fact, this term is overused by the community to define strategies that we dislike playing against, or to define an archetype that is usually just the natural predator of famous and widely played decks. Breaking a format requires specific factors, not just the displeasure of a portion of players in relation to a certain strategy.

As mentioned earlier, because of its nearly thirty-year history, Magic has its own standards and patterns — which also represents the possibility of evaluating and establishing the common elements among most strategies that break competitive formats.

Their results are predominant

This is natural for all “best decks”: they will have more positive results than the others and will be commonly parked around 10-15% of the Metagame share, with these numbers being able to fluctuate up to 20% in some formats.

Usually, a broken deck generates some different effects, such as its predominance reaching 25, or even 30%, while other competitive archetypes tend to be below 10%, or we usually have it with 25% to 30% and another that has a positive matchup against it with around 10 or 15%, demonstrating a polarized two-deck Metagame.

Another point that we must also consider is the representativeness and the general win rate that the “best deck” has against the rest of the format. If it appears in excess in the Top 32 of the Challenges for having a very favorable win rate against basically the entire Metagame, it is very likely that the format needs to adapt to play against it, and if that doesn't happen in two or three weeks, we are probably dealing with a broken deck situation.

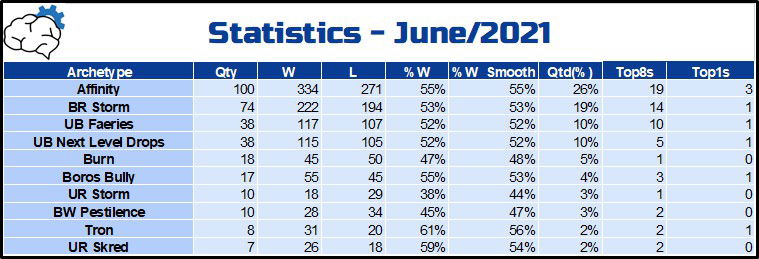

A classic example of this was the post-Modern Horizons II Pauper in 2021, where Storm and Affinity basically accounted for more than half of the Top 32 of basically every tournament at the time.

They usually cheat in game mechanics

Broken decks are not built to play fair, but to take advantage of some ability or new card that allows it to get ahead of opponents, usually by breaking some game rule.

In some cases, this is incredibly obvious, as was with Four-Color Valki, which even led to a rule change to Cascade itself.

In it, the player resorted to spells like Violent Outburst and Ardent Plea to cast Tibalt, Cosmic Impostor for just three mana, allowing the player to accumulate an absurd amount of card advantage that would normally be coupled to a seven-mana Planeswalker.

In a general concept, Naya Winota fits right into this category where, with the right setup, you can cheat multiple mana costs by putting Tovolar's Huntmaster and other creatures on the battlefield for free, merely by having Winota, Joiner of Forces in play.

Ad

Other ways of cheating in the game mechanics also include the famous “free win” button, specifically those that allow an instant win with a combo.

That is, easy-to-build combos that win the game instantly, or create an irreversible board positions — Splinter Twin, Dimir Inverter and Izzet Epiphany are some examples as they were rather easy to assemble and hard to play around.

Finally, another element still related to combos are those that wins the game too quickly: Your combo can, sometimes, win the game on turn 3, but when it happens too often, you're breaking the natural flow that a Magic match should have by forcing all opponents to answer you before you can win, automatically creating an oppressed format.

They are incredibly difficult to interact with properly

The harder your deck is to interact with, the more problematic it becomes. Either because of the lack of good answers for what you propose to do (something very common on Standard or Pauper), or because your strategy is too redundant and requires an excess of interactions to even allow opponents to play fairly against you.

Pauper, for example, can't handle Storm well because it doesn't have efficient means to avoid the ability's triggers, like Flusterstorm or Mindbreak Trap, so all winconditions of that archetype have been banned.

Likewise, if your opponent needs to resort to multiple copies of maindeck hate against your list and/or dedicate multiple Sideboard slots specifically for a matchup against you, chances are that you're playing a broken deck.

The fun factor

The "fun factor" is not a unique element related to broken strategies, but it is another point that commonly leads to the banning of certain cards.

In recent years, fun has often been considered by Wizards of the Coast when banning cards in an attempt to maintain their proposition that Magic games need to be interactive, fun, and exciting for both players, and this leads to the banning of cards that promote anti-game situations, such as the combination of Karn, the Great Creator and Mycosynth Lattice in Modern's Tron, Teferi, Time Raveler in Pioneer and, especially, Cauldron Familiar in Standard for creating a dull and tedious experience for the opponent in Magic Arena.

So, while this doesn't classify a deck as broken, consider whether the game you're proposing is interesting and healthy in its interaction with your opponent, or if it makes the fun factor one-sided and, unfortunately, that's precisely what leads many players to naming strategies they find unpleasant as “broken”.

When is it worth building a Broken Deck?

I emphasize that the ideal solution doesn't involve simply giving up playing the best deck if you want to get the best results. When asked for a recommendation on what someone should play in a specific tournament, I always say that the options are:

1) The deck you are most used to play — You will have an amplified knowledge of how to behave in the most important matchups, and your experience will reward you.

Ad

2) The best deck in the format — There's a reason it's at the top of the Metagame, and with some practice, you'll definitely be able to play it well and your experience will be beneficial for future tournaments.

3) The best “free win” button — Sometimes, when in doubt about what to play with, the best option is to choose the archetype that ignores what other opponents are doing, since that way you guarantee good opportunities to win out of nowhere and reap some good results from unprepared decklists. This is especially useful in mid-sized tournaments with an open Metagame.

When choosing to pilot the best deck, we need to understand that the price of this can be much higher than just the monetary investment, and you need to be ready for direct interventions if your list performs above expectations in several tournaments or, when like demonstrated above, it presents problematic patterns for the diversity and amplification of that format.

I'm guessing your question at this point must be, "so when should I decide to build that deck that's doing great tournament results?" — For that, I created a general analysis guide that you can take into account when deciding to invest your money.

Do you have the cards?

Obviously, the more parts you have from the list, the easier and less expensive it becomes to assemble. It is very common for longtime players to already have a huge card pool of that specific format and only need one or two playsets to build a new deck.

In short, the fewer cards and less money you need to invest in building that archetype, the more likely you are not to be so harmed if some pieces are eventually banned.

This topic also leads us to another essential question:

Consider the cards' longevity outside the deck

How useful is the base of the deck you're building outside this list?

Let's review two examples:

When Thassa's Oracle and Heliod, Sun-Crowned were released in Theros Beyond Death, there was a consensus that they would enable powerful combos in the format, and it didn't take long before Dimir Inverter and Mono White Devotion grew in the Metagame.

As a combo-hybrids lover, I was amazed by this new era on Pioneer and wanted to build one of them: at the time, I already had an extensive pool available with good cards from different archetypes and some fully assembled decks. When evaluating the decklists, I chose to build Dimir Inverter because I only needed Inverter of Truth, Thassa's Oracle and Jace, Wielder of Mysteries — The rest was already available in my pool and /or I would buy anyway since they were useful in other viable strategies.

Dimir Inverter had Thoughtseize, Dig Through Time, Kalitas, Traitor of Ghet, Fatal Push, among several other parts that could be reused if the combo was banned and that helped me a lot to build other decks in the future.

Mono White Devotion, on the other hand, only had Walking Ballista, Nykthos, Shrine to Nyx and a few other spells that hardly saw play outside this strategy, while Nykthos and Walking Ballista were also played only on Mono-Green Devotion.

Ad

That is, consider whether the cards you'll need to acquire will have other uses outside the deck you're building, and even if they happen to be useful in other competitive formats, in case you have to sell them in the future.

That wasn't the case for Naya Winota: Although Fable of the Mirror-Breaker is a multi-format staple and Esika's Chariot makes occasional appearances, most of its pieces are relatively expensive, worked almost exclusively for that particular archetype, as without the ability to cheat on mana, they didn't do enough to justify their usefulness on Pioneer.

Know how to identify the problem

A broken deck doesn't come out of nowhere: something makes it problematic, and it's usually a card or a combo. Knowing exactly where the problem is helps to understand what can and cannot be banned based on our experience during games.

In some cases, identifying this problem is relatively easy and won't require much effort: everyone knew after just a few weeks that Oko, Thief of Crowns was above every Planeswalker released so far.

In the same way, everyone already imagined that Treasure Cruise would break Legacy and other formats by basically making room for an Ancestral Recall to exist for an easily circumvented additional cost in eternal formats.

In others, this issue is complex and difficult to interpret through common sense: the banning of Prophetic Prism and Bonder's Ornament (although the latter was already considered problematic) was an unexpected alternative to bans from Pauper to weaken Tron, but which worked incredibly well for this purpose.

However, everyone was aware that its existence was unhealthy and limited diversity by a wide margin, we just didn't expect that another ban than Urza lands would solve it.

On most occasions, the hive mind sense, the content creation and the game experience itself will lead you to better understand the situation and assess what the real problems are.

When identifying this problem, consider whether your investment will be too high when building your deck in the event of a future intervention and how much you will lose monetarily as a result.

Evaluate your goals

Ultimately, what is your goal playing this format? What tournaments do you intend to participate in, what are their prize pools, and when will they take place? Do you want to participate in Qualifiers and other big events, or are you just looking to play at your local store one Friday night a week?

Especially if you're starting out in the format or building a deck from scratch, it's not worth investing heavily in a broken strategy that can be banned in 90 days — it's an absolute waste of time and money, and you're unlikely to get the desired return within that time frame since the weekly in-store tournament prizes aren't usually very high — so wouldn't you rather invest in another top-tier strategy that isn't on the brink of banning?

Ad

On the other hand, if your schedule allows and your goal is to grind tournaments and climb the competitive landscape, playing Qualifiers and other big events, you'll likely recoup your investment in some time and be able to enjoy the best the format has to offer by ruthlessly crushing your opponents for being one step ahead of them in power level terms.

I know, many times we want to build a deck merely because we like it, and I can't disagree with that option because I would never have played Death's Shadow in 2017 if I followed a rational and logical line. Again, if you really want a deck which is nearly on the unfair play category of the format, build it, but be aware of the possible consequences and sometimes reconsider if you wouldn't be making a better investment by building another safer archetype.

"But my deck isn't broken, it shouldn't be banned!"

To wrap things up, one last topic I would like to mention in this article is that the human mind is extremely treacherous and self-conniving, creating all sorts of anecdotal evidence to convince us that our beliefs are proven facts that we are right, above any occasion.

In this case, when we are the person playing with the oppressive deck, we will never admit that it needs to be banned, or we don't know how to recognize the problem it poses to the format's health, and we only consider that opponents don't know how to play against it. While this possibility is real on some occasions, on others it is just a lie that we tell ourselves to deny the probable reality.

But when we're piloting a broken archetype, we know it and get this feeling every game — we feel like the opponent is a step behind, we feel like we're doing something absurd, we realize they're trying too many things to at least have a fair match against us — we know we're on high ground, and we're taking advantage of that because it directly affects our sense of competitiveness, as matches are made easier either by our opponents' desperation or mental fatigue, or by the clear difference in power level.

These points are even more evident when we are the ones who are facing the broken deck, so I recommend playing a few games against the best deck and doing an honest reading of the game to understand how powerful it is, and why it is in that position.

Noticing the signs and having that honesty with yourself and the game you love so much allows you to make better decisions about your purchases and sales within it, as well as collaborating with choices regarding your own posture inside and outside the game, as well as a better understanding of competitive Magic.

Conclusion

That's all for today.

I hope, with this article, I could better clarify the community's view on how formats break and what we can do to mitigate the damage that bans can cause in the return of organized play.

Playing the best deck in the format comes naturally to competitive Magic. But when it has clear advantages over the rest of the Metagame, it has consequences — and we need to learn to accept it, or predict when the ultimate price might fall upon us.

Ad

If you have any questions, feel free to leave them in the comments and I may return with a second part of this series.

Thanks for reading!

— 评论0

成为第一个发表评论的人