Hello readers.

In the last chapters of this series, we conceptualized the different types of Commander and drew a profile of what the “typical casual gamer” would be. Now that we have that in mind, let's finally start addressing a more practical topic that you've been waiting for: deckbuilding.

When it comes to Commander, this is a broad topic, full of particularities, as deckbuilding in a casual format tends to be something very personal. There are several factors that influence both the process and the result of building a deck, and one of the biggest questions raised by many players who think about an authorial deck is:

Where do I start?

Today we're going to talk about some concepts that can help you get started on building your Commander deck: motivation and orientation.

If you have no idea what these two words mean in this context, no problem. Both concepts are little or nothing known by the general community of Commander, but they are quite used even if instinctively by most people who think about building an EDH deck. With this article, I intend to put them in evidence, so that the next time you tinker a list you will go through them fully aware of what you are doing and thus optimize your decisions.

Let's get started then!

Motivation

Motivation is the reason you are building your deck. It sounds trivial, but it's not always that simple. You may be building a deck because you caught a glimpse of a specific commander and liked it a lot, or because you felt the need to focus on a certain strategy as it will allow you to play better against the strongest deck in your group.

Stories can be as variable as the people who play them, and it's impossible to list them all. Still, identifying the motivation behind building a deck is the first step towards correctly targeting the choices that will make it satisfying at the end of the process.

Some examples of common motivations for Commander decks:

- The favorite commander: “I really liked this commander. I want to build a deck around it.”

- The Unexpected Foil: “I opened a booster pack and came a foil Brago, King Eternal. I was tempted to build a deck with him.”

- The Upgrade: “I bought/got a pre-constructed and I really liked the deck, but I think it could be better, or I'm not satisfied. I intend to optimize it to harness its potential.”

- The Pet Card: “My favorite card is Warp World. I really wish I could use it in a deck.”

- The Meta Hate: “My group has a strong tradition of using counterspells. I wish I had a deck that was particularly effective at playing against that.”

- The Combo Player: “I discovered that there is a series of combos involving the card Helm of the Host, and I'm building a deck based on that”.

An immense variety of motivations can be obtained just by substituting and adding variables in the previous examples. When considering building a new deck, you should ask yourself, “why am I building this?” Your deck's motivation will give you the first clue on how to start building it. In other words, having this information clear in your mind will help you determine what orientation (see below) is right for your deckbuilding.

As simple as this motivation may be, it can become more elaborate during the deck construction process, serving as a guide for the addition or subtraction of new cards or strategies. For example, a deck built around Helm of the Host might have Godo, Bandit Warlord as a monored commander. However, a deckbuilder might also consider adding white because of the equipment tutors, in which case Aurelia, the Warleader would be a viable commander option. In both cases, there are combos and signature cards that also use both Godo and Aurelia, but don't necessarily need Helm of the Host. You can add some of them to have alternate combo lines for your deck; or you can choose not to do this if you want to avoid focusing so much on combos, using only the additional combats as an alternate victory line.

It is natural that, as described in the example above, new layers of motivation are added or removed as the deck building process presents new paths to be followed. Eventually these bifurcations can overlap and generate sub-motivations — ideas within ideas — that have the potential to divert you from your original goal so that at the end of the process your motivation ends up completely transforming.

These roundabouts are part of the most fun part of the deck building process, as they can lead you to a satisfying and unexpected result, on the other hand, they may also become distractions and end up getting in the way. Therefore, as much as it is good to always keep an open mind for new possibilities that may arise, it is equally important to also establish some criteria so that you do not end up getting lost along the way.

There are some tips to help you in this process.

First, create “rules” that set limits that you are not willing to cross, or courses that you want to take. Try to relate them to the type of game you are looking to try or your principles as a player. If you don't know exactly what kind of gaming experience you're looking for, the first chapter in this series can help you find out. Also try to be specific. General things like “I want a strong deck”, for example, won't help you to keep a cohesive line, unless you have a clear and specific idea of what a strong deck looks like (which varies according to the reality of each player). It's also important not to set too many rules, as the more you create, the more limited your deckbuilding will be. Freedom is an essential factor in this step.

Some examples of deckbuilding criteria:

- “I want the commander to play an important role”

- “I don't want my deck to depend too much on the commander or any other specific card”

- “I don't want combos in my deck”

- “I want some combos in my deck”

- “I want to be able to test different cards from the ones I've used a lot”

- “I want a deck that wins when attacking with creatures”

- “I want to use specific cards”

- “I don't want to use specific cards”

- “I want a deck with low mana costs”

- “I want a deck with many efficient answers”

- “I want to use only proven effective cards, without anything too experimental”

Another tip is to keep a record of all the motivations in your deck. Write down your initial motivations and as new ones are added, you include them in this record. If it is possible to create a scale of importance between them, even better. This will help you to have a clear and organized view of the deckbuilding process and if you need to remove any of them the less important ones would be the main candidates.

Orientation

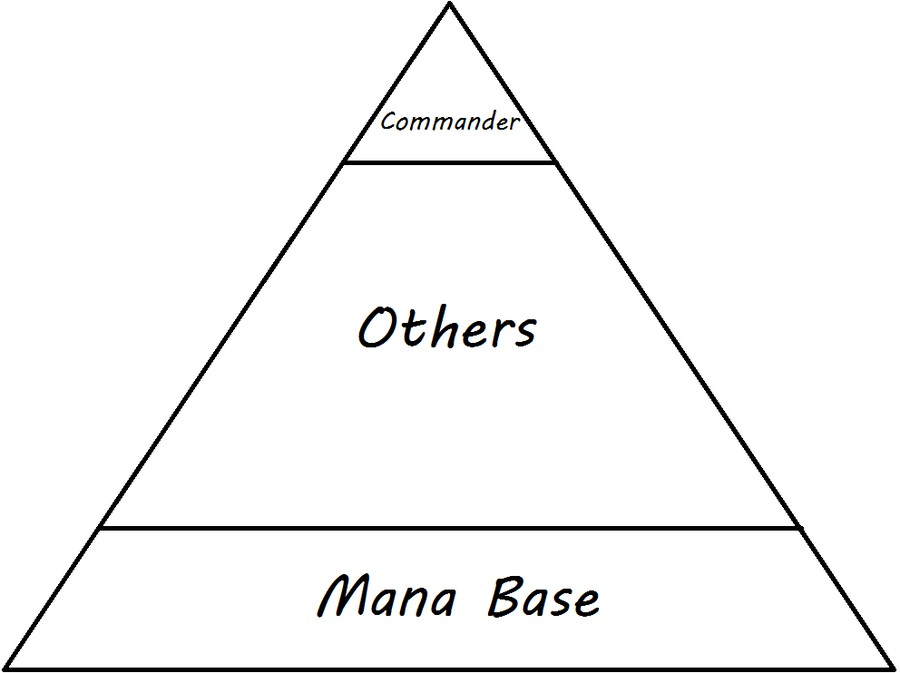

Orientation is the first step towards building the deck itself. It basically defines what will be the starting point around which your strategy will take shape. Once you have a clear idea of what your deck's motivation is, it will be easy to define your orientation. There are two types of orientation, and to make it easier to understand their concepts, we will use a representation of a Commander deck in a pyramid format.

Imagine that, in a hierarchy scheme, the commander of your deck occupies the place at the top of the pyramid. It has a guaranteed place there, as every deck needs one, and it will define the deck's color identity.

Lands - which make up what we call the "manabase" - occupy the base of the pyramid, as every deck requires them too.

The rest - the middle of the pyramid - will be occupied by all the other cards that will occupy the deck's functional packs. Note that the schema does not mention specific information such as quantities. It is not defined who will be the commander, if they will even have an important role or how many lands will be used. This will be defined by your motivation and in other stages of the process. That said, we can build the deck from top top-down or from bottom-up.

Building a Top-Down Deck

A deck built from the top-down considers the commander to be the strategy's definer. These decks will start with the commander's choice, and from there most of the strategies and other cards will be defined. This is the most common way to start building a Commander deck and the most recommended for beginners, as the commander itself is often suggestive enough to give some idea of what kind of deck it is possible to make with it, although this is obviously not a rule.

If your motivation involves building a deck for a specific commander, or if you've decided to start with choosing a commander, you're building a Top-Down deck.

Building a Bottom-Up Deck

A deck built from bottom-up goes the other way, when one or more specific cards or strategies are defined before the commander is picked. The starting point here is usually a specific theme or combination of cards that will be tied to the deckbuilder's motivations, from which the strategic core of the deck will be formed. Choosing a commander is only part of this process.

This is a less common form of deckbuilding in Commander, as it requires a more comprehensive initial understanding of what the deck should be able to do. However, as a player becomes more experienced and knows more cards, building Bottom-Up decks becomes just as intuitive as the reverse.

Orientation Variations

It is possible that while you build your list, your orientation follows the ideas flow and alternates between Top-Down and Bottom-Up at various times as new motivations are added or changed. A deck that started out being built from the top down may at some point be faced with the possibility of a specific strategy that would have enough impact to put the commander's position in check, and the reverse is also possible.

However, overall guidance is a more relevant concept during the early stages of deck creation, as a way to help you take that first step (which can sometimes be difficult). Once that's been done, and you've “hitched” into this flow of ideas, knowing which direction you're following is no longer so important.

Conclusion

With this article, we officially begin our journey into the ins and outs of deckbuilding in Commander. I'm really excited about this project and looking forward to your feedback. See you in the next episode with more interesting concepts to discuss.

— Kommentare 0

, Reaktionen 1

Sei der erste der kommentiert