Of all the things that make me like Magic: the Gathering, I see Commander is the main reason. After the first contact I had with the format, in 2012, all other ways to play Magic completely lost their fun.

Also, building decks was always one of my favorite things (maybe even more than playing). However, when I started in Commander at that time, and quite a while after that, one thing bothered me deeply. There was a profound shortage of didactic and specific deck building content in Commander. There were even some texts in English that deigned to talk more about the subject, but all were full of colloquial terms; - like ramp, fixing, stax and things like that - not bothering to explain them. There was almost no material that developed deckbuilding more comprehensively. It was always very specific, and the content aimed at laymen was practically non-existent.

Despite this difficulty, nothing stopped me or my group mates from evolving in the most efficient way there is: playing! Putting together decks that look incredibly cool, playing with them, and discovering that they're actually gross; this is an excellent way to learn from your mistakes. Weeks, months and years playing Commander with different players, building different decks. It made me develop my own method. Still, I never stopped looking for external references on other players, websites and forums.

This article is the first in a series of content that I have been producing with the aim of conveying the result of everything I have absorbed about Commander along the way. Originally, I had planned to organize all this material in a book format - a compendium of useful information that will serve players ranging from the layman to the more experienced. Talking to the Cards Realm team, however, we agreed that it might be interesting to split everything into an article series and publish them here on the site. So in the coming weeks we'll cover different deck building methods as well as concepts that will help you better understand the Commander format as a whole, so you can create your own deck building style.

This is dense content that has been scrutinized as much as possible for the reader who really wants to expand their knowledge of the themes and concepts used recurrently by the Commander community. This appreciation for detail is what justifies the choice to cover the subject in several articles, rather than a "quick guide to how to build a deck". It's not just about answering common questions like "how many draws or removals to run", for example. What I intend to do in this series is precisely to approach the most complex theoretical concepts and translate them into a didactic language so that even the most beginners can understand, but without failing to add to the intermediate or advanced player.

This article is episode 0 of this series: an introduction to the world of possibilities we are about to enter. A way to understand Commander, knowing its origins, evolution, main qualities and the reasons that led it to become the most played Magic format today.

Elder Dragon Highlander: A Brief Story

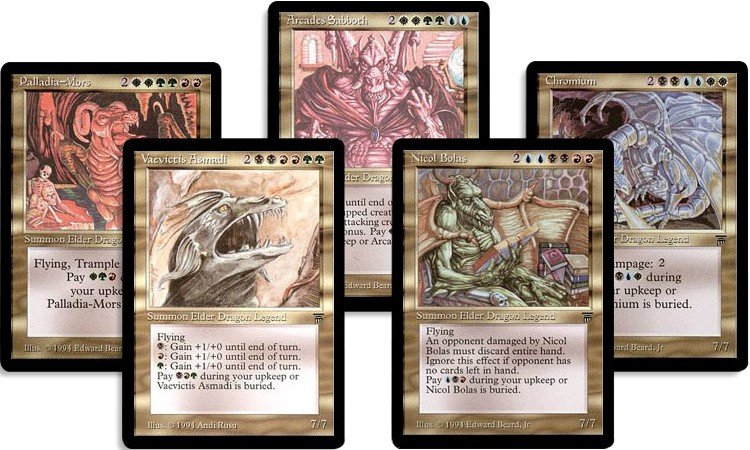

In 1996, in the state of Alaska, USA, a guy named Adam Staley created his own way of playing Magic. Named Elder Dragon Highlander (or EDH), the creator's idea was to promote long and epic games where unusual and less played cards had a chance to shine. The rules favored this: high life totals, decks with 100 cards, only one copy of each card could be used, and the presence of one of Legends' elder dragons (Nicol Bolas, Arcades Sabboth, Chromium, etc) as the "commander" of the deck.

Years later, the format was slowly becoming popular and being spread by several enthusiasts, including Sheldon Menery, a professional Magic judge who worked at major events around the world. Between refereeing one match and another during these championships, Menery played EDH tables with his peers to pass the time. He made some format changes (setting the starting life totals at 40, allowing any legendary creature to be the Commander, creating a banned list, among other things) and was largely responsible for spreading it. Elder Dragon Highlander gained more and more supporters and grew a lot in the judge community, and then among kitchen table players. All this at a time when Wizards of the Coast (the game's publisher) practically only supported competitive formats such as Standard.

At one point, around the latter half of the 2000s, Wizards understood that the casual gamer was an important part of its consumer market. The company then decides to launch a series of special products aimed at this audience. Encouraged by the success of Duel Decks, they decided to release products made specifically for multiplayer games, something they had never done before.

Thus came the sets Planechase in 2009, Archenemy in 2010 and Commander in 2011, all released during the American summer of the respective years and with the same purpose: to test the response of these casual players. The first two, Planechase and Archenemy, were Wizards' own creations, eventually drawing on casual formats from the game's own community (Chaos Magic, for example, was clearly an inspiration for Planechase). The third was fully used from the existing EDH mentioned above, which was already widespread at the time. All rules of this multiplayer format (created by Staley and improved by Menery) were kept, the only change was the name changed from Elder Dragon Highlander to Commander for commercial reasons.

The commercial response to these 3 products was reasonable, but Commander stood out among them due to the great spontaneous adherence to the format by players around the world. Commander 2011's preconstructed decks weren't such an explosive bestseller, but the EDH format became even more popular thanks to the visibility that product gave it. It didn't take long for the Magic community to realize that Commander was a phenomenon, and it was here to stay.

The format has grown exponentially in several countries to the point that it has drastically changed the representation of casual players, moving towards becoming a better defined niche within the Magic: the Gathering community. Stores that had pounds of stranded cards in their stocks suddenly found themselves faced with a growing demand for old, forgotten singles like Sol Ring, Demonic Tutor and countless others who were destined to never see play again somewhere. Their time was coming back, as they were not only legal, but excellent in Commander as well.

Wizards of the Coast got the message and did what they expected: they announced a second edition of Commander decks that was released in November 2013, two years after the first. The ad was acclaimed, and the set was a success. From then onwards, a new edition of Commander would be released every year and the format would not stop growing in number of followers. Today, according to Wizards of the Coast, Commander is the most played Magic format in the world, with a vibrant and segmented community. It became so big that it extrapolated the very basic principles of being a kitchen table format, attracting several other player profiles. A number of other formats come from it: Duel Commander, Leviathan, Tiny Leaders, Oathbreaker, Brawl... all designed with the aim of adapting the best features of EDH to different play styles.

However, despite its vast breadth — which is largely due to the high replayability and ingenious design of the Magic: the Gathering game itself — Commander remains hegemonic as an essentially casual format, which is one of the reasons for its monumental success. But why that? What exactly explains the EDH/Commander phenomenon, and why has this format taken the lead among kitchen table players over any other existing format? To answer this question, we need to better understand who is the main driver of this change: the casual player.

The Casual Player's Logic

When we talk about the “Magic community” we are referring to a mass of people who obviously share a hobby, but not exactly the same motivations and interests towards it. Simply put, different people play MTG for different reasons. There are studies that categorize the different profiles of MTG players into some personality archetypes, but the most widespread and popular form of distinction is between Competitive vs. Casual.

Most people differentiate both of these profiles as follows: The competitive player is one who plays to win, while the casual player is one to have fun. While these are the most entrenched definitions, they are simplistic and downright imprecise. Yes, the competitive seeks victory first, but he does it because that's the way he enjoys himself (so, fun is an end too). Likewise, the casual player values fun, but is not necessarily indifferent to the possibility of winning. What distinguishes casual from competitive goes beyond the win vs. fun axis.

For a long time, before Commander was a hit, being a casual player meant belonging to a broad group of people who didn't necessarily play a defined format. While the competitive player might say that he played T1, T2 or Extended, for example, the casual player might not be sure what to answer if someone asked him which format he played. Some even tried to keep up with the T2 (Standard) in their own way, but most simply used the cards they had regardless of the set and often didn't even know about the existence of formats. Many played multiplayer and optimized their decks for that, others didn't like it and therefore didn't have suitable decks for that.

It was a real Tower of Babel. Playing casually meant speaking your own language in terms of community, and this ended up further isolating that type of player into small groups. Still, while they didn't agree on the best way to play the game, casual players in general always shared certain values about the game.

The Unpretentious Game

Magic's complexity makes it possible for minimal variation between different courses of action (such as attacking or not attacking with a creature) to define victory or defeat in a game. Like any sophisticated activity, the ability to do well in these situations require good reasoning, coolness, and a thorough understanding of the game and its rules.

Such situations usually require a lot of concentration on the part of the players, making the game consequently more tense, especially if there is something important at stake, such as the awarding of a championship. Most casual gamers aren't comfortable with the tension inherent in competitive play and prefer not to get too caught up in the need to always make the best play possible. Obviously, this is not a rule. A casual player is just as capable of solving problems and devising incredible plays as a competitive one; but in general, he will at least be more open to making the play that makes the game more fun, even if it is not the "best".

Note that the concept of fun can be player-to-player relative. What is considered a good play in one group of casual players may not be in another (land destruction is an example). This subjectivity is not seen in competitive environments, for example, where the play that would bring a player closer to victory will always be desired. Still, sitting with friends, eating snacks and playing a Magic in a relaxed way amidst laughter is something valued by any player, even the most competitive. But for the casual gamer, this is the only fun way to play.

Multiplayer is a Social Game

It's not unanimous either, but the multiplayer tradition - the famous “meson” has always been very common among casual game groups. Tables with 3 or more players are a practical solution to simultaneously insert everyone interested in playing, without having to make pairings for duels. Furthermore, in the case of Magic, multiplayer games inherently adds the element of interaction between players that will have a direct impact on the game mechanics, possibly making it more “political”.

In one meson, for example, two players might slug it out in a two-way feud (“I'll attack you with my strongest creature just because you've countered my spell!”) while a third player just watches, getting stronger as their opponents battle between themselves. Likewise, players can form alliances with each other to defeat an opponent who has become too strong, and the like. This considerably transforms the dynamics and logic of the game, making it entirely different from traditional Magic played in a two-player matchup.

Of course, the nature of the meson also makes it quite difficult to use this model in competitions, as a single malicious player — or two or more colluding players — can completely unbalance a match, which would not be desirable behavior in most competitive environments. This further reinforces the stereotype of multiplayer as a casual game mode, even though it doesn't necessarily dominate the niche.

Creativity Freedom

One of Magic: the Gathering's great design merits is its replayability; that is, its ability to remain interesting even after being played several times. One of the things that allows this is the huge variety of existing cards and the possibility to combine them to create a countless number of different strategies. This modular quality of the game allows players to imprint their own personality on it, by building a deck, for example.

This practice of treating deckbuilding almost as a form of expression ends up being supplanted in competitive environments, since in them the options are limited only to the most efficient cards and strategies. Although creativity is still widely used by competitive players, in a context where winning is the most important objective, the ability to play with decks tends to bring more results than the ability to create them.

Those who refuse to give up this creative freedom in building their own decks end up becoming casual players. They understand that they are giving up the best strategies created by others for the personal satisfaction of playing what they find most original, interesting, or fun.

The Power of Flavor

Another great attraction of Magic: the Gathering is the fantastic theme covered by the cards. The term flavor exist to cover all the cosmetic part of the game that is not directly related to mechanics or strategy. Flavor is used masterfully by game developers as a tool to make Magic a much more attractive product.

Through the beautiful characters, creatures and art depicted on the cards - as well as all the fiction created around them - the game has an effect on the imagination of its players. This reinforces the collecting factor and keeps them emotionally attached to their cards. Certainly, flavor is so powerful that it is capable of influencing deck creation or strategy. Casual players are often more susceptible to this influence than competitive players, who typically choose their cards and strategies based on their effectiveness.

The Secret to Success

If casual Magic was a formless niche until the late 2000’s, things definitely started to change after the release of the first Commander decks. Many casual players were attracted to that game mode, whose rules favored all the qualities they most cherished. The main and most defining of them, in my opinion, is the fact that it is a format essentially designed for multiplayer matches; which in itself is already an attraction and so much for a good part of this audience as previously mentioned.

However, being a “meson” format is not the only reason for its high adherence. Here is a personal analysis of each element of the Commander rules and the reasons why this format is so attractive to so-called kitchen table players:

1. Players choose a legendary creature as commander for their deck.

The commander's rule is perhaps the most emblematic of the format. It evokes the principle of flavor power, as it establishes a legendary creature (which in theory would play a major role in some story) as the avatar of a deck. When a match is about to start and the commanders are put on the table, it's reasonable to imagine the following: “Okay, these characters are about to fight each other and each one leads an army. Let the war begin".

2. A card's color identity is its color plus the color of any mana symbols in the card's rules text. A card's color identity is established before the start of the game and cannot be changed by game effects. Cards in a deck cannot have colors in their color identity that are not in the deck commander's color identity.

This is a rule that also serves the purpose of enhancing flavor, as its main purpose is not to allow deck building to deviate too much from the commander's essence. However, by limiting the options on what can and cannot go into a deck based on color, it also creates the need to resort to workarounds for certain cases.

Swords to Plowshares is a great removal for creatures, for example, but a Commander deck with Titania, Protector of Argoth won't be able to use it. This leaves players often forced to resort to their own creativity, using unconventional cards to solve problems that in other cases would be easily solved simply by adding mana sources of other colors.

3. A Commander deck must contain exactly 100 cards, including the commander.

4. Except basic lands, two cards in the deck cannot have the same name.

In MTG, there is an unofficial rule about deck building that many players follow: don't clog your deck of cards. It is math-driven and makes a lot of sense for most formats where there is no maximum size limit for a deck.

If a deck has many cards, the probability of a specific card being drawn is lower compared to one that has fewer cards. The same logic applies to the number of copies of the same card: the more copies, the more chance it will come on a draw. It's common for players in most formats to use multiple repeating cards and squeeze the total deck size down to as little as possible (usually 60 cards), in an attempt to make it more consistent.

Rules 3 and 4 serve precisely to break this logic in Commander and promote unpredictability and diversity in the game. When you only have one copy of a card in a deck, it has fewer chances of appearing, and when the deck has 100 cards, the odds are even smaller. This contributes for the variance during games to be much greater and for a great diversity of cards to interact, allowing a greater participation of all players and making each game unique.

5. Players start the game with 40 life.

The obvious purpose of this rule is to increase the duration of games. More life totals, more playing time. More playing time, more fun. "More fun" in this context means "more chances to make that crazy play you imagined when you were building your deck, but which would only be possible if you combined many cards and/or had a lot of mana". When you are in a multiplayer environment, this increase in game duration is even more potentiated. As a general rule, long games also allow for more participation and interactions, while also allowing for more creative freedom.

6. Commanders start the game in the Command Zone. While a commander is in the Command Zone, it can be cast, subject to normal time restrictions for casting creatures. Its owner must pay {2} each time that was previously cast from the command zone; this is an additional cost.

7. If a commander is in a graveyard or exile and that card has been put into that zone since the last time state-based actions were checked, its owner can put it into the command zone. If a commander is placed in its owner's hand or library from anywhere, its owner can put it in the command zone. This replacement effect may apply more than once to the same event.

Rules 6 and 7 enforce the commander's position as the central figure in a deck. Ensuring that the commander is your most accessible piece underscores not only its strategic value but also its flavor, bearing in mind rules 3 and 4 and the impacts they have on gameplay. The command zone works as an extension of a player's hand, so if the commander has been there since the beginning of the game, creating a strategy specifically designed for him makes a lot more sense.

This allows a Commander deck to acquire a themed personality supported not only by the Commander's flavor but also by its mechanics, as well as opening up several possibilities for distinct themes that are only possible in the format (we'll talk about them in the future).

9. If a player has suffered 21 points of combat damage by a Commander during the game, that player loses the game.

This rule had a minor impact on the format's success, although it is one of its trademarks. Although it is somehow anchored in the flavor and helps the commander occupy a special place among the other cards, in my opinion, it serves more as an ornament that adds to the other qualities highlighted by the previous rules.

Still, the commander damage rule has a relevant impact on gameplay, as it offers an alternate victory condition in specific cases where one or more players reach superb amounts of life totals, something quite recurrent in the format. It also supports aggressive decks (based on dealing damage with creatures) which, in general, have a very high difficulty in Commander compared to other formats, due to the much higher amount of life points, and there are usually three other players to deal damage to.

Conclusion

After all, what use would this article be for someone who wants to improve their game or their deck building? Why is it important to know why a specific format is interesting? This should be intuitively perceived, right?! I mean... If a game is fun, it's fun and that's it! How can this reading help you to be a better player?

Well, beyond the simple curiosity to know a little more about the origin of the format you play, the content of this article might seem unnecessary. But see, on the other hand: no matter what your interest in Magic, if you play it is because you are seeking fun to some degree.

However, the concept of fun is broad and can vary from person to person. As much as the Commander/EDH was created targeting a specific type of player, with specific preferences, I believe it has hit a much larger number of targets, gaining a far wider fan base than it has ever been and much more than its creators could ever imagine.

With this article, I hope I have helped you understand this process, and that you have glimpsed part of your role in it. Knowing what kind of player you are, as well as what amuses you... this is the next step on the journey.

See you in the next article!

— Kommentare 0

, Reaktionen 1

Sei der erste der kommentiert